This article is an English translation of this Norwegian article – The views expressed in the article are solely those of the author.

Auditors spend a significant amount of their time gathering audit evidence. Both the quality, quantity, and time spent on this process can be improved with a new technique called Triple Entry Accounting. In this article, I will explain the concept of Triple Entry Accounting and how it can greatly assist in the execution of audits. No technical background knowledge is required.

Auditors can gain more resources

In the 2019 annual report of the Norwegian Financial Supervisory Authority (Finanstilsynet), it was noted that:

“Violations of good auditing practices were found in all cases reviewed. The most serious breaches were that the auditor had not obtained sufficient and appropriate audit evidence to substantiate the audit report. This also applied to audits of public-interest entities.”1

I noted this statement because it indicates that auditors sometimes lack resources. As a former auditor, I understand how demanding the annual closing process can be, where time is of the essence. Additional resources could take the form of new technology, improved skills, or more auditors.

Triple Entry Accounting is a new technology that has yet to be adopted by the accounting and auditing industries. The most notable large-scale application of Triple Entry Accounting is the Bitcoin blockchain. Blockchain technology, though primarily known as a speculative instrument, has demonstrated exceptional traceability and security over the past 15 years.

What if we could leverage the security and traceability of blockchain technology to create innovative tools for the accounting and auditing industries? This article explores this question.

No, Triple Entry Accounting will not replace auditors. However, it can automate many routine and time-consuming tasks. Audit evidence from third parties can be collected automatically in large volumes using digital signatures. This can improve audit quality and reduce costs.

Triple Entry Accounting lays the foundation for seamless digital processes for reconciliation in accounting and auditing, rather than forcing manual processes into a digital format. It does not replace double-entry bookkeeping or existing accounting systems—it is an extension, similar to a bank integration within an accounting system.

Continuous auditing also becomes feasible with Triple Entry Accounting. This could ease and distribute the workload throughout the year, providing better oversight during audit planning and the annual closing process. It could lead to less overtime, better-rested auditors, and, ultimately, easier retention of staff.

Innovation often occurs at the intersection of multiple disciplines. A multidisciplinary approach provides insights into both the problem (resource-intensive processes for collecting sufficient and appropriate audit evidence) and the solution (what is technically possible and legally compliant). This article first offers a conceptual understanding of blockchain technology. Then, it explains the concept of Triple Entry Accounting and how it can be implemented in practice. Finally, it examines the regulatory clarifications obtained during participation in the Financial Supervisory Authority’s regulatory sandbox for fintech in 2021. “The regulatory sandbox allows companies to launch new, innovative products, technologies, and services under the supervision of the Financial Supervisory Authority, which also clarifies the necessary permits.”2

But first, we take a brief journey through the history of accounting technology, from Single Entry Accounting, via Double Entry Accounting to Triple Entry Accounting.

Historical Overview: From Single Entry Accounting to Triple Entry Accounting

Single Entry Accounting

Single Entry Accounting is a simple recording of events as they occur. It is the most basic form of accounting, essentially just a list of entries. For example, it could be a list of transactions, such as those seen in a bank account statement.

Single Entry Accounting was poorly suited for measuring profits and tracking liabilities. It also lacked control mechanisms to prevent errors and fraud.

Double Entry Accounting

Double Entry Accounting addressed the shortcomings of single-entry systems. Wealthy merchants in medieval Italy adopted this method, which provided a superior information system. With reliable data on profitability, assets, and liabilities, they made better business decisions than their competitors.

Double Entry Accounting involves recording two entries in different accounts. The first entry documents what happened, while the second entry explains why it happened. These entries must balance.

Example:

- What happened? Inventory increased by 10 NOK (debit).

- Why did it happen? Debt to the farmer increased by 10 NOK (credit).

These paired entries were kept in separate ledgers and sometimes even managed by different accountants, creating strong internal controls against errors and fraud.

Double-entry bookkeeping is the same method used by modern accounting systems today. However, it has two key weaknesses:

The first weakness is the possibility of alternative and fictitious accounts being created and presented to different stakeholders. Such fraudulent practices are difficult to detect and represent one of the oldest tricks in the book, remaining a challenge even in modern times. Notable examples of this include the Bernie Madoff scandal and Enron, which led to the downfall of the auditing giant Arthur Andersen.

The second weakness is that accounting information remains difficult to reconcile with third parties across disparate data silos.

Triple Entry Accounting

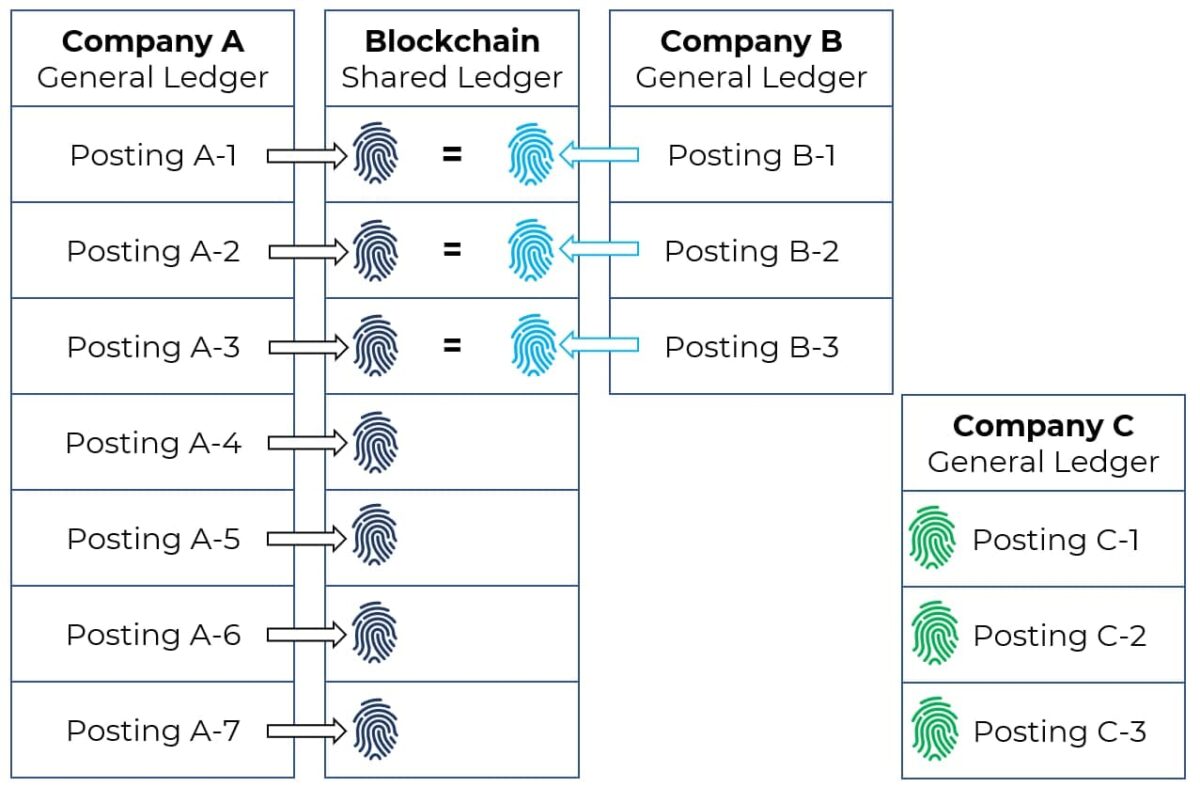

Triple Entry Accounting solves these weaknesses by extending double-entry bookkeeping. A third entry is recorded in a shared ledger, such as a blockchain. This third entry enables verification of data consistency across the same ledger and facilitates reconciliation across silos.

What is a Blockchain?

The term “blockchain“ often creates confusion. A more accurate name might be «Time chain». A blockchain is a publicly accessible data structure, functioning as a secure, tamper-resistant ledger designed for easy verification and auditing.

This type of “ledger” has seen increasing use in recent years for securely logging transactions of digital currencies like Bitcoin. A blockchain generates a timestamp for new entries at regular intervals, which is a key aspect of the system’s security and has been a hallmark of blockchain technology since 1991.

Most importantly, blockchain technology employs a unique security mechanism that makes it extremely difficult to manipulate or alter digital files. This mechanism involves the widespread publication of verifiable “fingerprints” of digital files. In this way, it is only possible to add data, not delete or modify it.

The timestamp proves that the information existed at the time it was published. Each timestamp is linked to the previous one, creating a chain of timestamps. The term “Time chain” would therefore be a more fitting name. The name “blockchain” derives from the fact that it consists of blocks of data timestamped sequentially at regular intervals. Think of it as a new section of information being added to a ledger (blockchain). Each new block contains a fingerprint of the previous block, forming a secure chain where manipulation can be easily detected.3 A useful analogy is to consider a new block as a “new page in the ledger,” where the outgoing balance on the last line of one page must match the incoming balance on the first line of the next page.

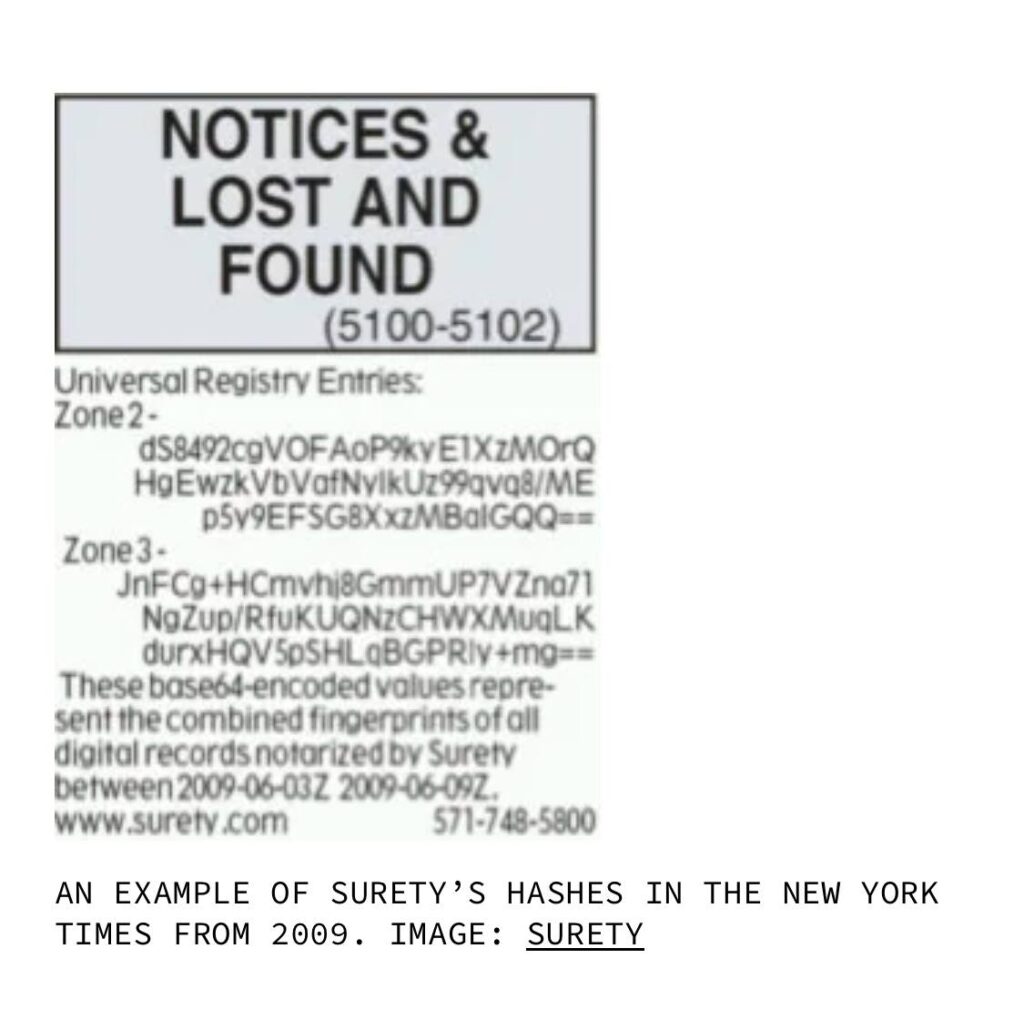

In 1991, Haber and Stornetta published the methodology for creating the first blockchain using newspapers.4 Newspapers are widely distributed and naturally dated (timestamped). A series of subsequent newspaper editions forms a chronological chain, which they described as a “chain of time-stamps.” The purpose was to develop a method ensuring that digital files could not be manipulated or altered. The process was briefly outlined in two steps:

-

Creating a Fingerprint (Hash): The selected digital files, such as documents and images, were reduced to a “fingerprint” consisting of 40 characters, called a hash. A hash function takes large files as input and produces small, unique fingerprints as output. If even a single character in the files is altered, the output becomes a completely different fingerprint.

- Publishing the Hash: The fingerprint (hash) was then published in the “Lost and Found” section of the weekly newspaper (see Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System and How to Time-Stamp a Digital Document for more details and illustrations). The newspaper was distributed widely to the public, including archives and libraries. The confidentiality of all original files was preserved, as the hash function is nearly impossible to reverse-engineer.

If the original digital files are altered or tampered with, the hash function will produce a different fingerprint that does not match the originally published fingerprint. Since modification or deletion is not allowed in blockchain systems, any inconsistency serves as a clear indication of tampering.

It would be nearly impossible to hack or manipulate these 40-character-long fingerprints across all the widely distributed newspapers, each witnessed by many. Blockchain utilizes this same mechanism digitally over the internet instead of through newspapers. This ensures that data on the blockchain achieves very high levels of security, integrity, authenticity, and availability.

Importantly, the security of the system does not come from the fingerprints (hashes) themselves but from their widespread publication and verification. If the fingerprints were kept hidden, this security mechanism would not function.

In summary, blockchain is a globally accessible ledger that logs information with timestamps, publishing it to a broad audience. The ledger is highly resistant to tampering and is designed to be easily verified and audited. These properties are instrumental in developing new technologies for auditing.

What is Triple Entry Accounting?

Triple Entry Accounting is characterized by the existence of a shared ledger, such as a blockchain (an open registry). In this ledger, a third accounting entry can be recorded with a digital signature, in addition to the two traditional debit and credit entries in standard accounting systems. This is the origin of the name “Triple Entry Accounting.” The third entry is referred to as a Financial Fingerprint. Since the ledger is open, these financial fingerprints are continuously accessible to auditors. Auditors can use the financial fingerprints stored on the blockchain (the shared ledger) as a source to verify the entries recorded in traditional accounting systems.

It becomes particularly exciting when two or more trading partners use Triple Entry Accounting, as the financial fingerprints from their respective ledgers can be reconciled with one another and used as audit evidence. This system has the potential to automatically collect vast amounts of audit evidence from external sources throughout the financial year. Any ledger entries involving a counterparty—such as receivables, accounts payable, loans, or bank transactions—can be reconciled through Triple Entry Accounting.

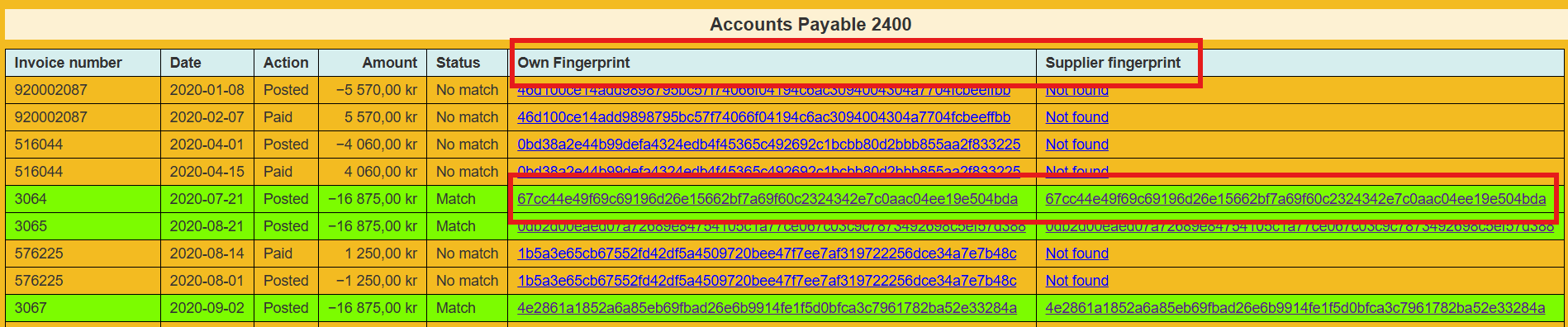

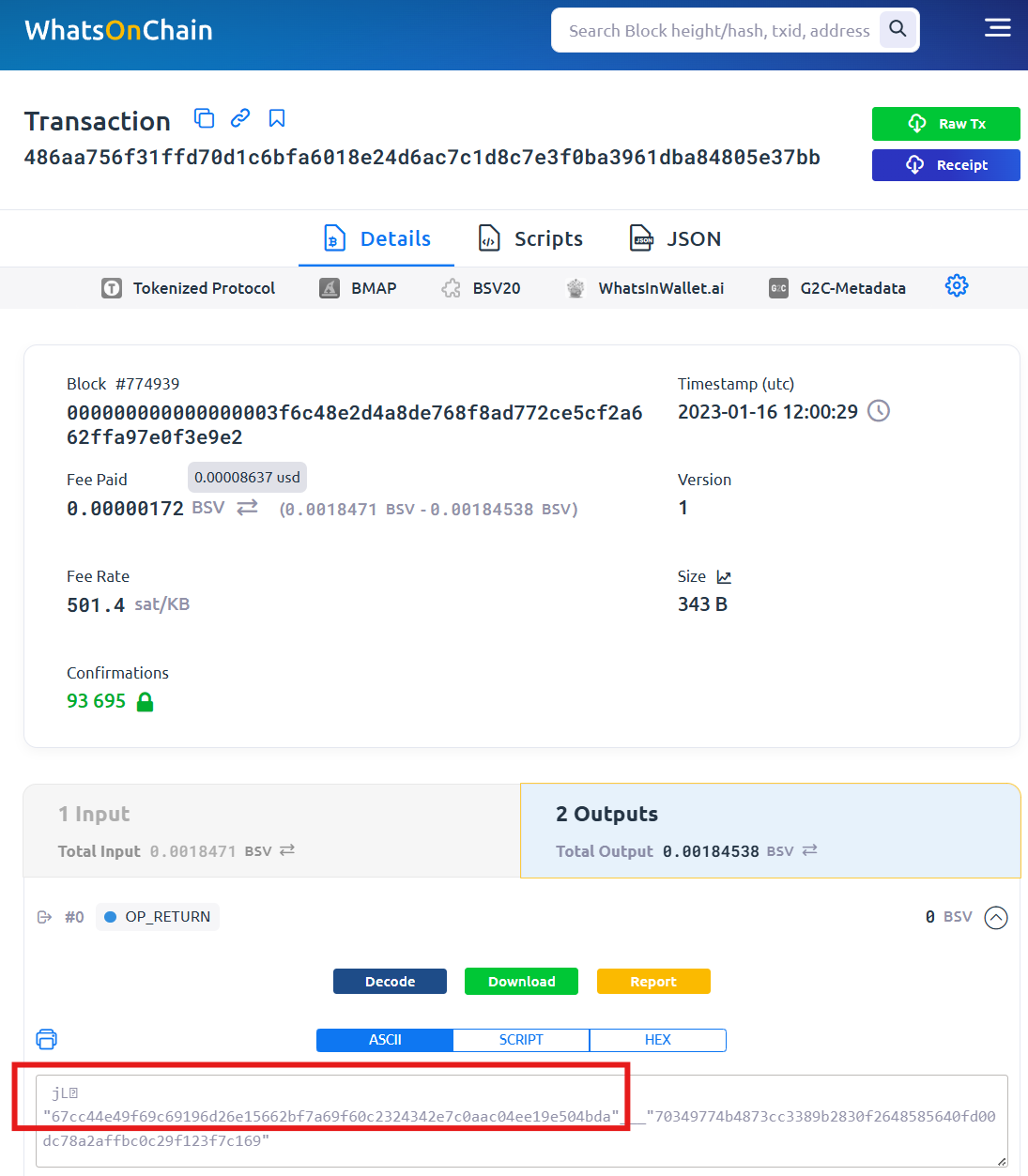

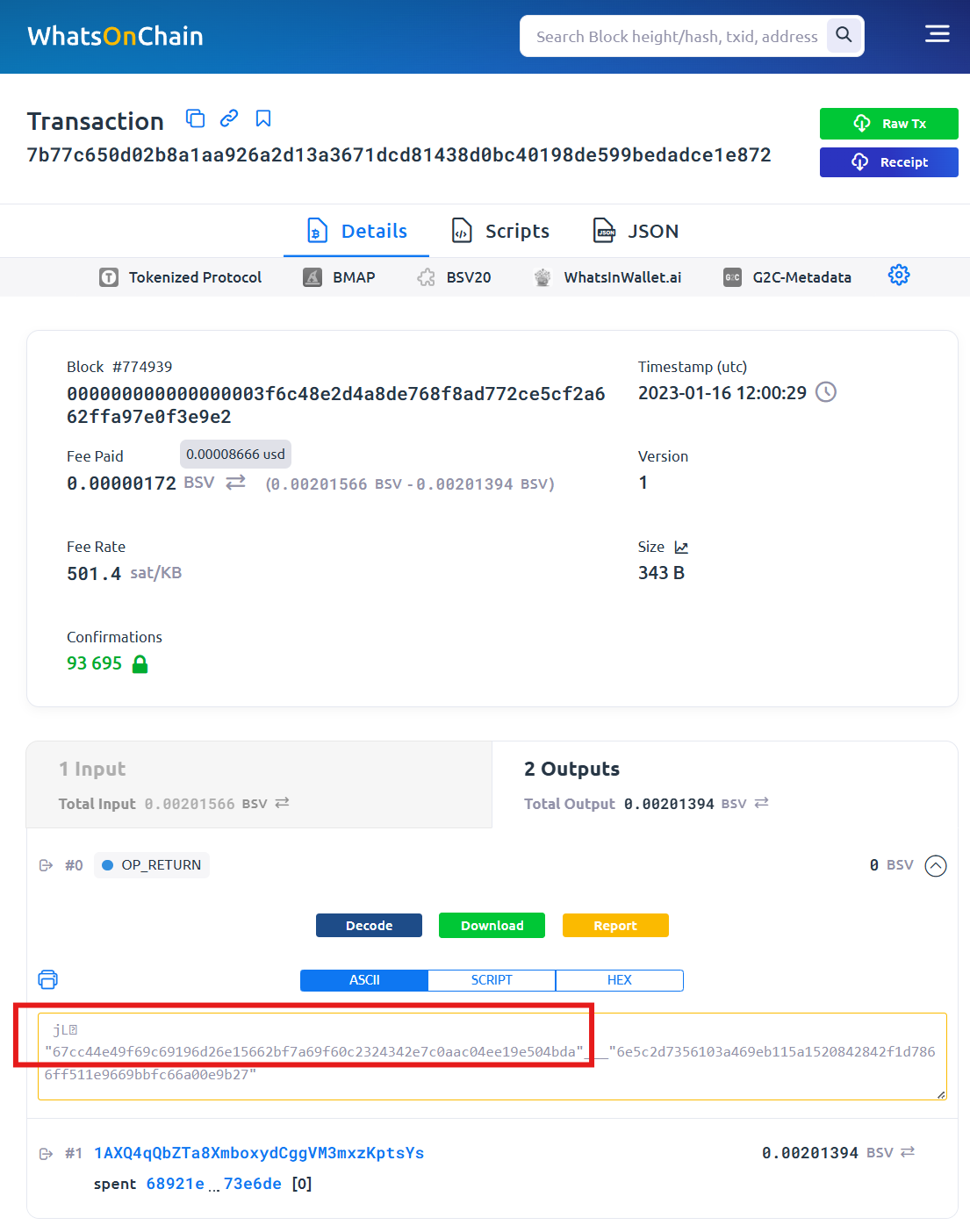

We have developed a prototype for Triple Entry Accounting. On the left side of the interface (screenshot 1), parts of ledger entries retrieved from an accounting system’s API integration are displayed. On the right side, the financial fingerprints generated by our prototype are shown. Green lines indicate matches, which can serve as audit evidence. This evidence comes from an external source and demonstrates that the trading partner has recorded the same transaction. By clicking on the hyperlink, the financial fingerprints can be viewed directly on the blockchain (as shown in screenshots 2 and 3).

This system is scalable and capable of reconciling billions of transactions.

Ian Grigg first conceptualized Triple Entry Accounting in his 2005 article. I came across Grigg’s work on Triple Entry Accounting during my time as an auditor in 2018. While he is a pioneer in this field, he has acknowledged that one of the challenges with Triple Entry Accounting is its reliance on network effects. A well-known example of network effect challenges is the first fax machine or early social media platforms. If there are no other participants in the network to communicate with, the system lacks value.

In 2023, Grigg organized the first Triple Entry Accounting conference (the next conference is scheduled for April 25–26, 2025; those interested can contact me for details). Ahead of the conference, I was invited to write an article. We presented a solution addressing the network effect challenges in our paper, titled “Implementing Triple Entry Accounting as an Audit Tool—An Extension to Modern Accounting Systems,” which was published in the Journal of Risk and Financial Management.5

How Can Triple Entry Accounting Be Implemented in Practice?

It is essential that Triple Entry Accounting operates automatically in the background and does not interfere with existing accounting processes. This means that it is sufficient for the CEO or financial manager to approve a one-time connection to an extension in the accounting software. When the auditor later conducts a review, they can be granted read-only access to a dashboard that shows the proportion of ledger entries matching those of an external party, such as a supplier or customer, who has also signed entries on the blockchain.

If the network effect is low, the auditor can request other third parties to integrate a one-time extension into their accounting system, connecting it to the blockchain. Initially, this may be most relevant for the largest suppliers and customers. This integration can save time for both parties in ongoing and future audits.

The auditor can also propose the use of Triple Entry Accounting to their client without affecting their independence. There is no risk of the auditor auditing their own work because ledger entries must be finalized before Triple Entry Accounting can begin. Regulatory clarifications about the role of the technology provider for Triple Entry Accounting will be addressed later in the article.

The solution to the network effect relies on three aspects.

First, Triple Entry Accounting must provide value before the network effect takes hold. By integrating accounting systems with the blockchain, Triple Entry Accounting can prove that all figures genuinely belong to the official accounts. In other words, if accounts are documented using Triple Entry Accounting, it will be impossible to present alternative accounts without detection. Presenting alternative accounts is one of the oldest forms of fraud, as exemplified by the Bernie Madoff investment scandal.

Second, the IT architecture must be designed so that companies can onboard independently and at different times, yet still reconcile their figures with those from previous financial years.

Third, it has been confirmed from a regulatory perspective that auditors can propose the use of Triple Entry Accounting to their clients and to third parties holding audit evidence that the auditor needs to collect.

Even a small network effect, where only the largest trading partners have integrated Triple Entry Accounting, will benefit the auditor in the initial stages.

The implementation itself is as simple as setting up a bank integration in the accounting system. The solution generates financial fingerprints and integrates them with the blockchain automatically in the background. Previous years’ ledgers can be integrated into the blockchain during onboarding, and future ledger entries will be continuously integrated into the blockchain. This facilitates a smoother auditing process in subsequent years.

The use of the technology in practice will not require any changes from accountants or financial managers working with day-to-day bookkeeping. However, auditors intending to use Triple Entry Accounting to gather audit evidence must have an understanding of the tool and the blockchain technology behind it to assess the quality of the evidence effectively.

The Financial Supervisory Authority’s Regulatory Sandbox for Fintech 2021 – regulatory clarifications on the use of blockchain for storing and providing access to audit evidence

What if we could utilize the security and traceability of blockchain technology to create new tools for the accounting and auditing industries?

The Financial Supervisory Authority (Finanstilsynet) found this question intriguing, and we were allowed to participate in its regulatory sandbox with our proof of concept. We encountered a forward-thinking regulatory body that recognized the potential of Triple Entry Accounting using blockchain to store and make audit evidence accessible in audit processes. Through this collaboration, Finanstilsynet gained a deeper understanding of blockchain’s use and was able to provide regulatory clarifications on the technology.

Auditors and accountants are subject to supervision by Finanstilsynet, making these clarifications critical for innovative professionals who wish to adopt this new technology. Below are some summarized excerpts from the final report. The full report, available on Finanstilsynet’s website, is recommended for further reading.

Below are some summarized excerpts from the final report. It is also recommended to read the full report, which is available on the Financial Supervisory Authority’s website. 6 7

ISA 500: Audit Evidence

“One issue with Abendum’s use of distributed ledgers and blockchain is whether the evidence obtained meets the criteria to qualify as an external source.”

“Summarized, the assessment is that audit evidence where fingerprints of a ledger transaction are matched on the blockchain can be considered an external source since the transaction is signed by a counterparty. The classification of audit evidence as an external source significantly impacts evidence quality.”

ISA 505: External Confirmations

“Since audit evidence in the form of ‘confirmations’ will be available in distributed ledgers/on the blockchain before the auditor enters the audit process, the auditor’s control over requests for external confirmations on the blockchain presents a new issue.”

“In principle, ISAs are intended to be technology-neutral, and this principle was practically tested in the sandbox. After thorough reviews and proposed adjustments to how the tool is used to gather data, the conclusion was that ISA 505, as well as other ISAs discussed in the sandbox, are indeed technology-neutral. It is possible to obtain audit evidence that can be classified as an external confirmation on the blockchain.”

ISA 402: Service Organizations and Outsourcing

Service Organization

“Abendum can function as a service organization for a company if its software is used by the company and the auditor intends to utilize this solution to collect audit evidence for auditing the same company.”

Outsourcing

“If the auditor enters into an agreement with Abendum and uses the tool while recommending that clients adopt it for more efficient audits, collaboration between the auditor and Abendum may constitute outsourcing, depending on the underlying contractual relationships.”

“In the sandbox, activities such as collecting, compiling, and presenting audit evidence from various sources, verifying data, and confirming source identities were identified as audit actions that could potentially be outsourced through the solution.”

ISA 230: Audit Documentation

“Audit evidence available on the blockchain can enhance the auditor’s capacity and ability to prepare sufficient and appropriate audit documentation in a timely manner.”

ISA 240: The Auditor’s Responsibility to Consider Fraud in an Audit of Financial Statements

“Audit procedures addressing management override of controls are critical because this is one of the few risks that is always present, as per ISA 240, paragraph 32. Therefore, the auditor must always design and implement audit procedures to address the risk of management override, as outlined in ISA 240, paragraph 33.

This procedure (comparing a list of transaction IDs from the blockchain against the ledger) does not depend on counterparties having to record or confirm transactions on the blockchain. However, it is a prerequisite that the tool is integrated into the accounting system before the financial year begins.”

Auditors Are Well-Suited to Understand Blockchain

Finally, it is worth highlighting that auditors are uniquely positioned, due to their education and experience, to understand blockchain technology as applied in society. A multidisciplinary approach is essential to comprehend both the potential and limitations of blockchain systems. Auditors possess expertise in law, economics, auditing, accounting, and IT systems—competencies that require time and maturity to develop. With a little additional knowledge of blockchain concepts, auditors are capable of understanding blockchain systems at a much deeper level than those who focus solely on the technical aspects.

Master in Accounting and Auditing, NHH

(Norwegian School of Economics)

Torje Vingen Sunde

CTO, Abendum AS

References:

- The Financial Supervisory Authority’s Annual Report 2019: Finanstilsynets Årsmelding 2019.

- Financial Supervisory Authority’s Regulatory Sandbox for fintech, including details on its purpose and functionality: Regulatory Sandbox for Fintech.

- Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System by Satoshi Nakamoto:

Read the paper here - How to Time-Stamp a Digital Document by S. Haber and W.S. Stornetta (1991):

Access the publication here - Sunde, T.V.; Wright, C.S. Implementing Triple Entry Accounting as an Audit Tool—An Extension to Modern Accounting Systems. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 2023, 16, 478.

https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16110478 - Final Report from Abendum After Participation in the Financial Supervisory Authority’s Regulatory Sandbox:

https://www.finanstilsynet.no/nyhetsarkiv/nyheter/2022/sluttrapport-fra-abendum-etter-deltakelse-i-finanstilsynets-regulatoriske-sandkasse/ - Abendum Final Report (PDF):

https://www.finanstilsynet.no/48f974/contentassets/49a4d8f284ad41bc8b3005db5bde1f57/sluttrapport-abendum.pdf

Leave A Comment